Work in Progress is an interview series with independent curator, writer and cultural worker Alyssa Alexander, that spotlights an emerging or mid career artist, allowing them to explore facets of their individual practices, share works in progress, and connect with overarching contemporary themes. Each iteration will have artists answer questions tailored to their work, but culminate with the same five questions.

Chantal Feitosa is a Brazilian American multidisciplinary artist and educator living in Queens, NY and working in Brooklyn, NY. Her works shift between new media and social practice, addressing themes like racial hybridity, western beauty standards, and belonging. Language, in particular, weaves thematically through her video works, Machine Learning Bias and Brown Bag Lunch, as the artist contends with the complicated social and political histories of Brazil. Here we discuss the nuance of naming yourself, the miscegenation campaign of post-slavery Brazil, and how Lorraine O’Grady is a complete badass.

Chantal Feitosa: So, I feel like this year has been really strange and just like recalibrating where I’ve being at with my practice, especially since moving into this studio I feel like, this is a very confusing position of trying to remember where my brain was at a year ago, and resuming where it started at the start of 2020.

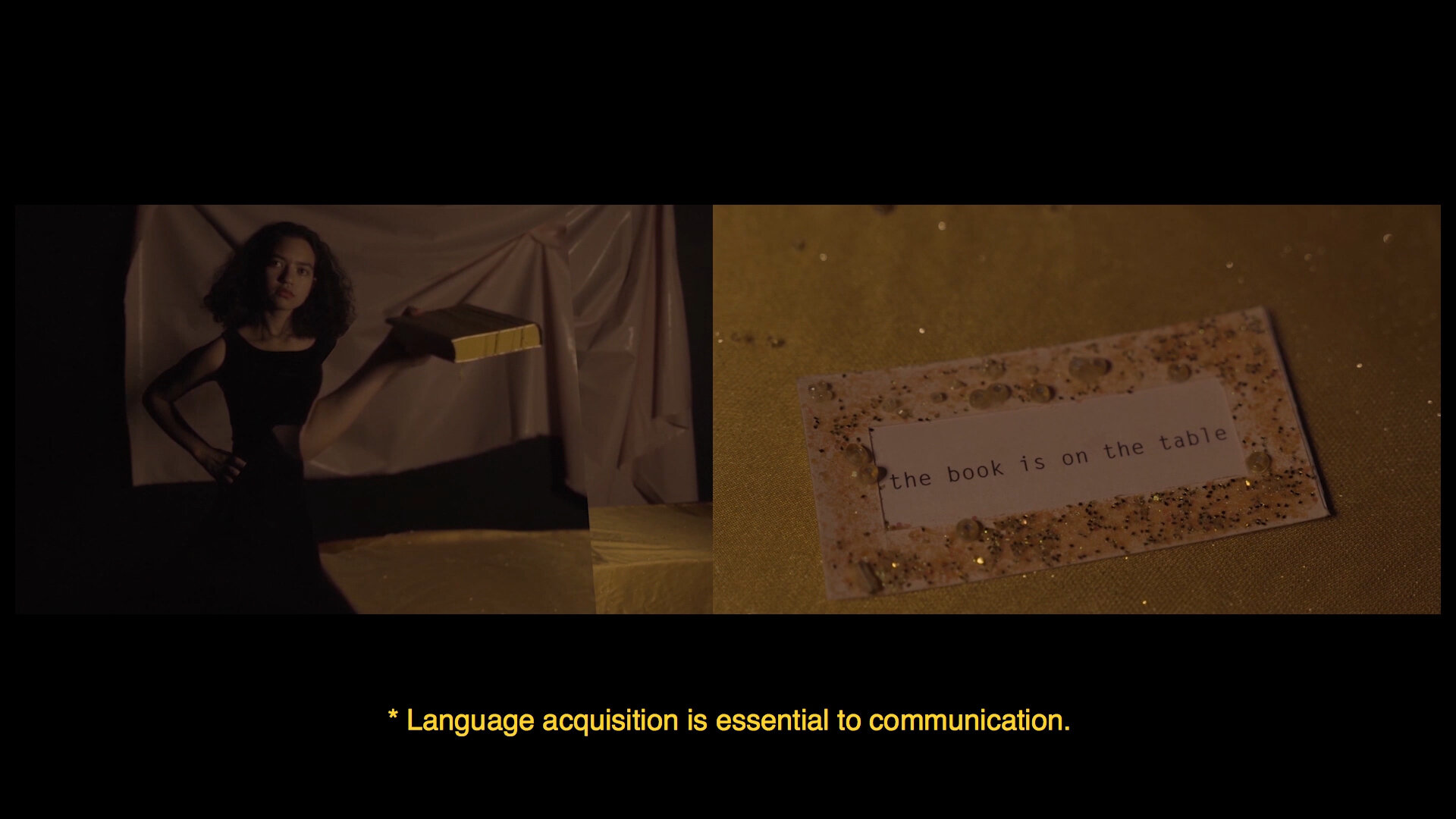

Like this video excerpt I sent you that I’m well underway with finishing, but it’s kind of weird when you take almost a year off for making something.

Alyssa Alexander: Do you usually take breaks when producing work?

Chantal: No, this is like the first time this has happened.

Alyssa: Naturally, I am not surprised.

Chantal: I think what is both the silver lining, but also really frustrating about that is, I think I’ve changed as a person over the course of the year, and then returning to a project with a different outlook, it’s helpful but it is also destabilizing. I look at this rough cut and I’m kind of like, wow there are so many things I can’t change because the footage has been shot, things are edited, but then because it’s still like 70% done I think about the audience in a different way.

Alyssa: That transition I guess is great for the actual reflection on the work, and it’s helpful for a viewer to know that, that you yourself changed in the midst of this work, and you are cognizant of that and it is part of the work almost.

Chantal: I mean just like other things that I’ve been starting, I’m also doing a lot of drawing and 2D work, I’m just generally interested in the different frameworks of how it is that we use language to connect with one-another, like the written science but also the verbal and physical, and does it create different systems for how we like to think about care or difference, and I’m thinking about these ways of thinking about language that are also informed my own upbringing.

Alyssa: Can you say a little bit more about how language plays a role in some of your older projects like the Machine Learning Bias work? That for me was probably one of the first ones that I encountered from you, and I had never considered language in that way.

Obviously, we know that language [as we know it] is a colonial construct for certain, but the ways that you investigated that within the work, especially within a language I’m not familiar with, that was really interesting. So, if you can get into a bit about how language has driven more than one body of work for you?

Chantal: So, there are a few reasons for that, and the first one I think I was interested in was this idea of this concept of naming things and how it is that we attribute names to people, places, and objects, and who is entitled to the right to name something?

Alyssa: Yeah, that’s an interesting concept.

Chantal: And even through time, the ways we think about how to name things whether, it’s identity, race, or even gender, or even nuance in geography, the concept of naming something is very much like something that exists almost out of time. I think about language and words, and the ways language is this thing that can almost time travel.

Alyssa: I see what you mean.

Chantal: One thing I started to get really interested in, especially with the Machine Learning Bias video, is also thinking about different systems and bureaucracies, even the education system enforces more of the oppressive ways that we think about language and use it.

Machine Learning Bias, 2018. Courtesy of artist.

Alyssa: In the ways we’re confined within that during our upbringing without saying “yes” to it, we haven’t authorized this constraint on our outlook, but because we’ve been roped into a system of language that is so overarching that we almost can’t escape it.

Chantal: One of the most frustrating things is not only language, but also the command of words, and how we learn to use them throughout the span of our lives, and even within the context of formal schooling there is so much power and privilege tied to being able to read and write.

But then there is also this idea of privilege and power that comes with literacy and legibility for people. I think when you exist in the world as a body that is othered, there is always a desire to be legible or broken apart, or be a text that can be dissected and indexed. So, I always think a lot about literacy and language within this double-edged sword of the need to be able to wield it, but also how we can reach a point that we can have a control of language? And also deny access to the ways in which people use it against us.

Alyssa: As a weapon, yeah. For me I think about growing up in predominately immigrant communities where that language barrier isn’t necessarily an issue on a day-to-day basis, it becomes that way when folks decide to employ language in a certain way. That part of your work has always been interesting to me, the concept of language being deployed in that aggressive and authoritarian way, when it is against a certain marginalized group, like in othered bodies, the way you were describing. What was the name of the video that you sent to me?

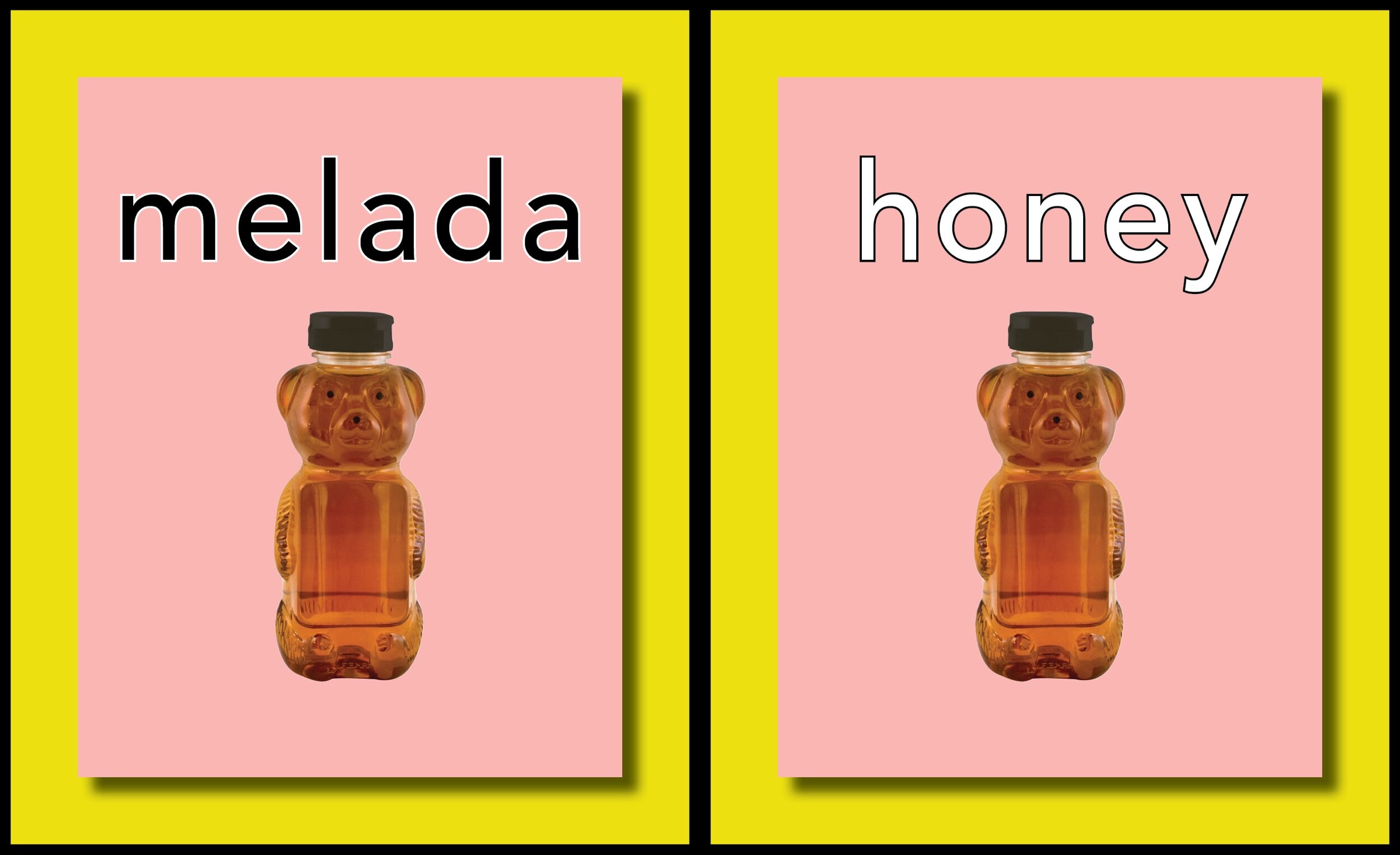

Chantal: That piece was called Brown Bag Lunch. As a point of departure from the Machine Learning Bias project, I still think about ways of creating these video performances that play around with these didactic ways of learning, especially with English classrooms and source material. So, even before I started thinking about how I wanted to produce this video I started creating these word cards that are similar to cards that you see in kindergarten classrooms.

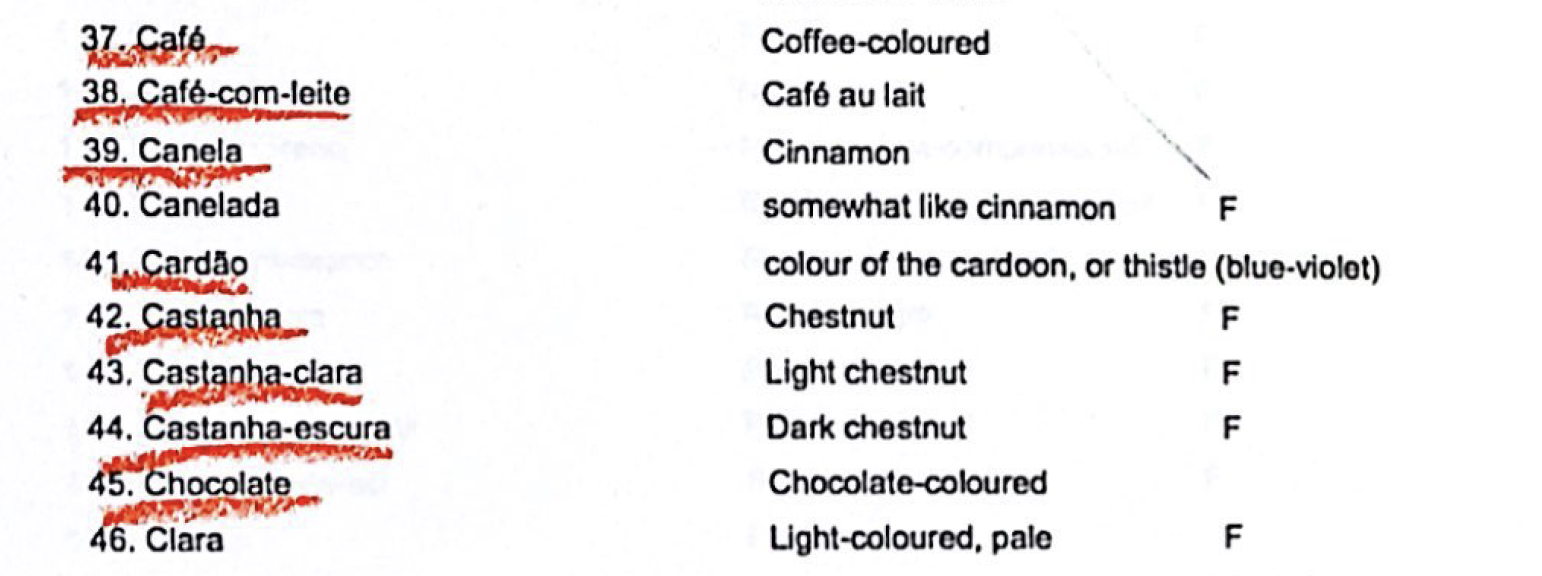

I started creating these English and Portuguese translations for food, and all of the terms that you see here are pulled from a survey that was given out to the Brazilian population during the 1970s. It wasn’t actually a census but it was tied to getting a snapshot of the demographics and general information on the population. When it came to the question of “racial identification,” the government gave people the option to write in whatever answer they wanted instead of just having like a standard multiple-choice option.

Because people could write in whatever they wanted people got super nuanced with how they identified. A lot of the answers that actually came back were terms very similar to food. People were saying and literally writing in like “chestnut.”

Alyssa: In terms of how they identified?

Chantal: Yeah, I was really interested in these very literal words people were using to see themselves. It also just speaks to the disparities of how, between the United States and Brazil, people think about differences between whiteness and blackness whereas, here [in the U.S.] it’s very binary.

Alyssa: I was going to say there is a range, in other places the nuances exist, it’s understood that it isn’t so Black or White. That’s a really good point, that does not exist here. In more recent years terms like Afro-Caribbean have gained popularity, which I guess adds more identifiers than African-American, just because culturally my family is not from here. So, Afro-Caribbean sounds more like it. But as a kid it was just “Black, non-Hispanic” okay that’s all I got, that’s the range that we have. But in other countries they view themselves within this range of diversity which is really impressive.

Chantal: I guess there are both upsides and downsides to that range too. I think it’s great there is this nuance, but sometimes you get too nuanced to a point, and sometimes I kind of question, well what is like the ends to calling yourself— like if you’re calling yourself “dirty white” is that just your way to like dance around the fact that you don’t want to acknowledge that you’re Black or mixed race? So yeah terms like that are really interesting. Are you just trying to find synonyms, instead of just calling things what they are?

I wanted to play around with the specific terms that specifically refer to food, and I started creating this digital deck with these words.

Alyssa: I was going to ask you if the foods were chosen on purpose but I hadn’t realized it was connected to the way people literally viewed themselves [laughs].

Chantal: From there I started to think about “Well, how is it that I wanted to activate these cards?” Even now I think about beyond just the context of this video, what are the ways in which this can exist in a different iteration? Whether, it’s something online or something physical, at some point in the future where we can touch the same art [laughs] safely someday.

Alyssa: When I saw the chestnut one, I thought about the way that kids, like my nephew who is four, we’ll say to him “Oh, you’re such a smart Black boy.” The first time he was like, “I’m not Black I’m tan.”[laughs] This whole conversation is so interesting to me because it’s so innocent, and you are really looking at your colored crayons and trying to figure out which ones we are [laughs].

Chantal: I think this idea of kids is interesting too because even from an early age if you’re not aware of the fact that the whole world is racializing you in some way, it can be frustrating when you are young, because you don’t have the language for that and you’re thinking about things in a very literal way.

Alyssa: Literally exactly.

Chantal: This painting is called Ham’s Redemption, it was made in the late 1800s in Brazil, right after slavery was abolished. One of the things that is also really different from abolition in Brazil versus here (in the U.S.), is that once enslaved Africans were freed, the government really started to have this awkward problem where the population of Brazil was mostly Black. Brazil was a country that had imported the largest number of Africans out of any of the colonized countries in the world, and there was a lot of anxiety with the white Brazilian elite, and they had fear of being outnumbered. So, the government started to promote a lot of laws to bring in more immigrants from Europe. There was this really big incentive for mixed races and inter-marrying.

Modesto Brocos, Ham’s Redemption, 1895

Alyssa: Wow, that’s bizarre.

Chantal: Like super different from here.

Alyssa: To meet the same ends honestly.

Chantal: To meet the same ends.

Alyssa: So like, “We want to get more inter-racial so we’ll kind of dilute the Black population”?

Chantal: That was basically the goal, and this painting kind of summarizes the general sentiment at least within the white class of Brazil, and it shows like the ultimate goal of this need to whiten future generations of Brazilians.

Alyssa: Was it successful?

Chantal: Well I guess in a sense there is success in that most of the population of Brazil is mixed race. But still the white demographic continues to be outnumbered.

Alyssa: They still are?

Chantal: But instead of being outnumbered by mono-racial Black people …

Alyssa: Right, the mixed population.

Chantal: That is 100% a by-product of almost 200 years of these policies that really enforced the need to just have everyone intermixing with this goal of trying to eradicate Blackness at least within the mono-racial sense.

Alyssa: That’s fascinating, I’ve seen with Machine Learning Bias, I’ve read some of your texts about that whitening campaign, promoting not only whiteness but whitening, and I know that Brazil has a very complicated history with colors. Is it a caste system?

Chantal: You could say it’s a caste system.

Alyssa: Like this scale of Black to white in terms of our society and how you move in society. I didn’t know there was an actual campaign to bring white in and dilute it. So, this painting is a reference point for the work?

Chantal: I also feel like you can’t really have survey responses such as this, where people are thinking about race in a way that is so broad and nuanced, but just not directly addressing race.

Alyssa: Right, you almost lose the race in it when you get all these kinds of answers. You should do this in America, you should totally do it!

Chantal: Just knock on peoples’ doors [laughs] …

Alyssa: You should put this survey out there and see how folks respond when they’re not forced to check boxes, but rather write in what they identify as; fascinating - fully support doing it.

Chantal: It’s not a bad idea [chuckling].

Chantal: Then they became like a source, like a jumping off point for the video where I wanted to find ways to re-interrupt this painting.

Alyssa: Oh, the gesture, I was going to ask you about that.

Chantal: So, back at Smack Mellon I had created and built, well this is like a still but the guy recreated the backdrop out of the painting but I wanted to recreate the composition of it. I’m also really interested in the central figure of the painting, as this woman in what she represents as an identity in a body. She problematizes the ways in which mixed-race people are like weaponized within this larger white-supremacist agenda.

Alyssa: Yeah, they’ve almost made her like a Mary for this new generation, and she births this baby that is going to be the new whiter Brazilian population, that’s insidious, wow.

Chantal: It's weird, yeah.

Alyssa: Was it like a popular painting at the time or is it something you just found in archival research?

Chantal: I found it through archival research, but there are actually a lot of people in Brazil who know about the painting. I think within Brazilian art history, which is also Euro-centric, this is a very well-known painting. Even across Latin-America because other countries in Latin-America also have this problem of needing to whiten future generations and this painting always gets referenced.

Just like the composition and the choice the artist made of having her be this central figure that is just like this vessel for birthing out white people, but also this figure that’s like awkwardly this threshold between the past and future.

Alyssa: Yeah, I think they literally set the composition to be this past and future, or I guess the baby is the future, the guy is completely creepy because of what he represents but also the way they positioned him in here. This sidelong glance at the baby, oh my god the longer I look at it [laughter] it’s getting more and more aggressively racist.

I see the woman to the left who I guess represents the past, I immediately felt bad for her because the set up seems like something is afoot with her there, like she’s either a domestic worker or something of that nature, or wet nurse of sorts but then you have to think she’s an older woman, and she’s probably of that generation that came over maybe. Who is the artist?

Chantal: Modesto Brocos, but yeah, there are things that are very like overt but also very subtle, even the differentiation of the ground. There is dirt and then this [gestures] is like modernity, it’s weird.

Alyssa: Even the choice of the light pink and the blue is very religious painting.

Chantal: Yeah, it’s super weird and then the child is like in a very Jesus style.

Alyssa: Is he holding an orange?

Chantal: Yeah, he’s holding an orange, which is maybe supposed to represent the world in the ways of paintings of like a baby Jesus is always holding a sphere. I wanted to remove this like mother figure from all these other people, and wanted to create almost like a satirical interruption of the painting where the woman who had to sit for this painting is on her lunch break, as she is sifting through the things she has for lunch.

All of these objects that she’s pulling out are these foods that represent these terms that were used in the survey, instead of holding this white child, she’s taking out these different foods, that are different identities, like further pulling out these future generations of Brazilians who might be White but are anything but white.

Alyssa: Then adding to that, the paper bag is also this kind of symbolic thing of race and kind of differentiating where you are in terms of shade. Brilliant, I’m obsessed.

Chantal: Oh, thank you. Yeah, she resorts to eating these different foods so that means also this idea of like eating your own people, or consuming your own culture, like force-feeding ideas that are imposed on you, which is also this idea of cultural cannibalism. That is also a big thing, how historically Brazil thinks about cultural production.

Alyssa: Interesting, expand on that? What do you mean?

Chantal: So, in the early 1900s especially when concrete poetry started to become a big thing in Brazil, there was this author named Oswald de Andrade who wrote this text called the Cannibalistic Manifesto. The text stems a lot just from these frustrations of just how I think Brazil, like constantly or at least like today in modern times, has this huge cultural identity crisis. We’re so miscegenated and so mixed as a culture, but also still very highly influenced by Europe. The text advocates for this need as Brazilians to just consume the cultures and ideas of other places, embody it and digest it and recontextualize it.

Alyssa: In order to find your footing?

Chantal: In order to find your own footing and your own identity.

Alyssa: The idea of consumption, is that seen in other works of yours this idea of consuming? Even with Machine Learning Bias there are some parts of it where the woman is eating, but it’s satirical eating, it’s not literally just eating—What was she eating in the video?

Chantal: There are like different pieces of paper, like cutouts from a magazine.

Alyssa: I remember the eating being somewhat uncomfortable because it was not meant to represent actual digestion of food.

Chantal: I wasn’t thinking so much about the specific ideas of cultural cannibalism we had in Brazil when I was making the first video, but yeah, I’ve always been really intentional with this idea of food. Like nourishment and all the different ways that it exits, especially when we’re thinking about language and how we ingest words and the ways in which words can sit in your mouth can either feel really good, and serve a positive purpose, but also do the complete opposite of that.

Alyssa: Ok, I’m going to ask you the five questions now. Take your time, you don’t have to answer immediately. People always get stuck on two of the questions specifically, so by all means you can come back to them if you don’t have the answer immediately.

Which artists are you currently most drawn to? What are you obsessed with? It could be an older artist, it could be something random, but what are you obsessing over recently?

Chantal: At the start of the month I saw Lorraine O’Grady.

Alyssa: I just saw it yesterday!

Chantal: It was so good! [laughs] Just like so good. I’ve known about her work for a while now. I think I first started learning about Lorraine O’Grady in either late high school or early college.

Alyssa: Wow you’re fortunate, I only just found out about her maybe two or three years ago because I was working at the gallery that represents her.

Chantal: Oh, my God, cool.

Alyssa: I got to meet her and she’s amazing, as feisty and vivacious as she comes through in her story and her work, that is literally her.

Chantal: That’s so cool.

Alyssa: She is one of the coolest older women I’ve met in my life. I can tell that she is interesting on levels that we probably will never know.

Chantal: I just distinctly remember one day Googling “Black Women Artists.”

Alyssa: As we all have. [laughs]

Chantal: The first time you do it, because no one at school is teaching it.

Alyssa: Absolutely, not.

Chantal: Like who are they? I then eventually came across Lorraine O’Grady’s work and just like this huge light bulb went off in my head, and I’m just like so in awe of how she is not interested in conforming to a specific idea of an artist who works in discipline, to an artist who works within a specific...

Alyssa: Even the type of photography.

Chantal: Yeah, even within a type of photography, types of performance, or even like her Black Middle-Class performance, the way she is not afraid to critique everything and everyone. She has this self-awareness and understanding that she exists between different spaces, and I think the way she navigates these in-between spaces is so brilliant, I think everyone should aspire to do that.

Alyssa: I was explaining to the person I went to the exhibition with that her identity is really complicated, that she’s investigating race, femininity, and inter-racial relationships and all those things. At first glance you can’t really understand the way she is unpacking it, until you understand that she walks around with that every day, it’s so heavily ingrained in her. It’s not that she’s attacking it, or like you said “critiquing everything,” in some ways she’s critiquing herself on a consistent basis, and that’s probably some of the best kind of work you can do, even as a non-artist, is to continuously reflect and think about the ways in which you exist in a problematic space. She definitely exists between worlds that are really fascinating such as this connection to Nantucket, or is it New England? She’s a very fascinating woman, but yeah, I just saw that show yesterday. I have thoughts about the way they displayed her work at the museum but we can talk about that off the record. [laughs]

If not working as an artist what profession would you pursue? Obviously, you’re an educator but something that is not art adjacent maybe?

Chantal: I think before I decided I would definitely one hundred percent want to pursue art, I thought maybe I would go into journalism. I think now as an artist I have found other ways of incorporating writing into my work. I think I would have enjoyed working within the media, but within a different context.

Alyssa: And interrogating language too, which is interesting. I have a degree in journalism.

Chantal: Oh, my god.

Alyssa: That is what I did for my undergraduate program, but similarly I was preoccupied with writing about art specifically, so I thought maybe there is something there and I’ve absolutely utilized it, and have continued to utilize the skills. I don’t know that hardcore journalism would have done the trick, I think I would have felt very boxed-in in that.

In your opinion what was the best moment for Black and Brown artists and their work? So, again, that’s kind of an abstract question, it could be a specific moment, specific time period, but a moment that was the best for them and their work?

Chantal: That’s tough, I’ll have to come back to it.

Alyssa: You can come back to it.

What is the last work that made you feel something, like positively, negatively, made you laugh or cry, but like a strong visceral reaction?

Chantal: So, a few months ago in the fall of 2020, I went up to Philly to the ICA and saw Milford Graves solo show, which I think was his last exhibition before he passed away. I just remember I was coming to that show, and was not in the best head space, like it was a weekend where I just needed to leave New York and go elsewhere.

Alyssa: See something else.

Chantal: Yeah, to see something else, and I just remember being so refreshed by all the ways in which he was synthesizing these ideas of silence, cardiology, music, and sculpture, it was a very multi-faceted practice. He had this one collage, I don’t remember all the details of it specifically, but it almost represented like a cardio-vascular system. It was this collage piece that had all these other different elements to it.

There are so few pieces that I spend more than a minute looking at it, but I think his work definitely surpassed that threshold. I don’t always see a lot of artists who are thinking very deeply about how to connect the mediums they work with, and how they are relating to their own bodies, but the way he connects the art form of drumming to human heart beats, it blew my mind a little bit.

Alyssa: This is me speaking freely, but I think your work is not exactly what it seems at first glance, like you really have to unpack it, and really make those connections. I’ve seen the videos and I've felt something that surpasses, like watching someone eat, and felt there was some connection to be made, that I needed to reflect a little bit more.

So, I guess that thought process in making your work kind of a reflection of humanity in some ways, in the ways that we exist and have that connection. It makes sense that that kind of work would make you respond in a strong way. Okay, last question and then we have to go back to one.

How if at all will your practice transform as we move towards a more digital based market? Now your work exists digitally to begin with but everything being super virtual, and virtual visits?

I still think that there is a need to experience your work in person, like watching it on a screen doesn’t necessarily translate the same way, but with NFTs and all these ways that we are leaving the physical space of viewing art, I just wonder if your work will transform at all, or if you reject that notion?

Chantal: I think there are ways it can transform, like I see it changing even beyond the work I’m wrapping up right now. But ideas that I want to start, that are inline to start up eventually. I like thinking about works that serve a better purpose existing online fully, but then also what does it mean to sell digital work online, that’s just an ethical question that I grapple with a lot.

The things I love so much about work that is digital, like time-based media is the accessibility of making it, but also the reach it gets to people. I think there is a time and place to put that type of work behind a paywall. So, those are questions I have for myself, where if I make things that are accessed fully online and benefit from being viewed online.

These are questions of accessibility that I’m thinking more about, and not only in the momentary sense but also how is it that people even engage with it, even in the sense of physical ability, but yeah, I’ve been thinking a lot about that, like I’m not super sold on NFT’s.

Alyssa: I think for artists it could be really liberating maybe or it could be a new frontier to experiment with, which I think is super important, but there is a part of me that is really pessimistic about what it means for someone like me who is more of an arbiter of art. I don’t produce art myself; I exist to connect folks with it or showcase it in a way that requires going.

So, when we cut out the middle man of the physical tangible item, I don’t know I feel weird about it, and strange that everyone is going crazy about it. I think for an artist it’s something to definitely explore, even messing around with it at first to just see what happens, like that seems useful. It’s just happening so fast and I’m seeing a lot of artists like “Oop, here they are, I did it in a day, I figured it out and you can buy it now.”

I also was really weirded out by how that beeple thing unfolded, where there turned out to be a lot of racist things in there that kind of went unnoticed because of the mad dash, to just consume, consume, consume, and that part was scary to me. We’re just in that mad rush to buy and to consume things. I’m not a determiner of what is good art and what isn’t, but there is something weird mixed in there that I’m not certain about yet, I need it to unfold a little more.

Chantal: I feel if you have done all the research on NFT’s and you realize that’s what you want to do okay, then that’s cool, like good luck I hope that works out. I think there are more people who are just not fully doing their research on what it means to invest in, like crypto-currency and are engaging with it, because it’s like this new thing. I feel with all new things that emerge digitally it becomes this bubble until it just bursts and there is no value.

Alyssa: I guess the way institutions are kind of taking it on so strongly makes it seem a little bit more sure-fire than maybe it is, like all this auction house backing seems like “Oh, if they’re doing it then obviously it must be something substantial” but I don’t think they know what is going on either.

Chantal: I don’t think so either. Yesterday I saw someone who minted an NFT of this pixel portrait of Breonna Taylor and I was like why?

Alyssa: Yeah, like why?

Chantal: So, now we’ve got to have work just like this that is going to come about.

Alyssa: That’s what I’m saying, I’m not here to determine what is and what isn’t art however; there are some things a lot of us can agree, is just being made for the moment, and exploited and weird, and isn’t anything to necessarily be invested in. It already exists out there and there are tons of people making stuff for the purpose of getting someone to buy it. I can’t imagine what the thought process behind the pixel portrait is of her, I don’t know. I can’t imagine they would grapple with anything for a great deal of time before producing that, so that is what concerns me, is it will just be this huge over saturation of just stuff and people will invest in that. Then by the time art that makes sense gets around to being on there, it will have already popped. Do you know what I mean? I just don’t know how sustainable the whole thing is.

I’m watching intently. I've tried to do as much research as I can, but it’s very complicated. The whole digital currency investing world is a huge mystery to me, so I’m just waiting for a solid breakdown so I can get on the right side of it.

I think it’s interesting especially for artists who already work digitally who have already grappled with certain complexities of that, or limitations of that, or negative things that come along with producing digital work. I’m just wondering constantly how you all are responding to this very, very big push for everything to be digital.

Chantal: It’s hard because you definitely have to tread with caution, especially artists of color, and especially I think if you're working with images of other representations, like art figures in some way. These are also things that I grapple with even with physical objects too, like I’m just maybe to the point where it’s also too much, just always thinking about the ethics or implications of what it means for someone else to be under the care of this representation of a body. Even if these aren’t real people like there is still this idea of —

Alyssa: They’re representative of, if not a person a people, do you know what I mean? Like a group, and it is difficult when it comes to other groups, like you were saying, because there is a lot of care and intention that has to be taken when you’re doing that, and then you put it out into a space where folks can do whatever with it.

I think as an artist that’s like a baseline issue that folks will take your things and do whatever they want with them, but definitely when producing figurative work that is representative of somebody in a metaphorical sense, I guess.

Chantal: There is this extra level, I think also that is complicated when it becomes digital like over the last like ten or twenty years. It’s just troubling how images of Black and Brown bodies are being transported across the internet and circulated, shared, and sold.

When that is replicated somehow through the art market then I think there has to be another conversation. How to do that responsibly? Is there a way to do that responsibly?

Alyssa: It is difficult and I’ve heard this from another person who just collects work, they felt oddly about having someone on their wall, like a photo of someone who they don’t know. I hadn’t really thought about that, and at this point I’ve collected at least three photos of Black men just living, because that’s what I’m interested in collecting.

I guess that’s problematic as well, making a disconnect with that being a living human-being that was photographed, and they are existing in my house in a way and I don’t know them.

Ok, what was/is/will be the best time for Black and Brown artists?

Chantal: That’s such a hard question [laughing] because I feel like … I don’t know if I can speak on time I was not present for but also … you know like I feel arguably now is the best time but then also maybe it’s not, like the best time is to come …

Alyssa: I think that’s a perfectly fine answer. [laughs] I’ve had folks respond and they think now more than ever artists kind of have agency they didn’t have before in terms of how they want to show up and even create work. Even if the artists in past or in previous generations were attacking the same thing, trying to get the same messages out, there is a little bit more autonomy now and more areas for that to exist in. But the fact that maybe the time hasn’t come yet is also a very valid point. So I agree with you and hopefully it is in the future, because I think there are roadblocks now even with all the so-called advancements and progression that’s happened.

Chantal: I also think this past year has just infuriated so many people and a lot of people are snapping way more than they would have pre 2020, and I think there’s so much more discourse on a mainstream scale. Like museums are racist, like yeah, like the staff of this one institution they really need to step up their game.

Alyssa: Lines are really being drawn in the sand more.

Chantal: Maybe just like questions of labor and organizing like I’ve heard a lot of artists just be like “Why don’t artists unionize? How do we do this?”

Alyssa: I guess that’s an important point where maybe the ideas that come out of this generation will make it better for future ones. Now again, this work has been continuous and there were things that were done generations ago that gave you the opportunity to even consider that. But yeah, I think there’s still a ton of work to be done, and it could be way easier for folks specifically Black and Brown artists to really make headways and real waves.